Any time I plan a trip, the first thing I do (sometimes even before I book a flight) is to start researching restaurants. By the time we arrive at our destination, I’ve usually built a bibliography of far more restaurants than any two people could possibly eat at. My restaurant researching is a practice born out of interest (I love learning about a city’s food scene), and out of necessity. Because my partner is celiac, we can’t just walk into any restaurant off the street and count on a meal that’s safe for his dietary needs. And ultimately, we want our meals to be much more than just celiac-safe. We want them to be memorable food experiences!

This winter break, we’ve been traveling, and so I’ve been alternating between working on my own research, prepping a research-based writing course that I’m teaching this spring, and of course, finding new restaurants for us to eat at. As I’ve been writing about my own qualitative research methodologies (I research writing pedagogy, not food), and as I’ve been thinking about what research skills and values I want to impart to my students, I’ve also been thinking about how my restaurant research methodologies have developed.

When I do research, and when I teach research, I want curiosity to lead, which means emphasizing the pleasure of discovery. In my current scholarly project, that means talking to teachers and visiting their classrooms. In the class I’m planning for spring, that means prioritizing student choice, and making time for human experiences like interviews and archival research. When I research restaurants, that means starting early so that I have time to explore, to get curious, to get hungry. (If I start when I’m already hungry, it’s a much less curious and more frustrating process). As a result, I do more research than is strictly necessary because I’m enjoying it. And we reap the rewards when the time comes to choose a place to dine out–even with a severe dietary restriction, we have options.

When I teach first-year writing, I’m reminded how much of research is about processes that we practice and refine over time. I have to take a step back to figure out how to teach my students the ways I’ve learned to adjust a search, the reasons that I move from wikipedia, to google scholar, to specialized databases, and back again. Over the years, I’ve developed a similar refined process for researching gluten free restaurants. This post is my effort to teach, or at least write down, my methodology. I hope that it will be helpful, not just for other celiac travelers, but for folks who work with other dietary restrictions too. This method could be adapted for vegan, for halal, for dairy free, or other constraints. Places that are good at accommodating celiac diners are also often good at accommodating other dietary restrictions (universal design is something that we talk about as teachers, but it can certainly be applied to the restaurant industry too). This is a methodology that I’ve used most in the US and Canada, but it could be adjusted for more global travel too–I’ve used it in Paris with some bilingual adaptations, and will be trying my best to research restaurants for a trip to Italy this summer. It’s worth noting that this works better in bigger cities, but we did apply some of the same strategies when we moved to Hattiesburg and were looking for safe and delicious places to eat.

The key to my restaurant research methodology is its orientation. When we first started traveling gluten free, I began my research with the restriction. Perhaps predictably, this led to few options, and often, some pretty mediocre food. Now, I begin by looking for good restaurants where I’d be excited to eat. Only then do I narrow the restaurants down to those that are also likely to be celiac safe. Here’s what both approaches look like in practice –I’ll use Toronto as an example, since it was the first stop in our winter break travel this year.

Restriction-first research approaches:

1. Searching on Find Me Gluten Free, the yelp of gf diners. In the early days, we used this a lot, but now, I use it mostly as another source to check the credibility of a restaurant’s ability to serve celiac-safe gluten free options. As a source, it has some important limitations: a relatively small user base, which means even in a city as big as Toronto, there may be only 7 reviews of a restaurant. It also tends to favor western foods and chains–you’ll see reviews of gluten free burgers, pizzas, and pastas, but much less of other cuisines that are more natively gluten free (more on that in a minute). In Toronto, the top 3 restaurants in my search look celiac safe, but they’re not the most exciting for a dinner out.

2. Searching “gluten-free” on google maps, or other mainstream restaurant apps like yelp. The advantage of this approach is a broader database of restaurants and users. I usually still do this as part of my research process for a city, because it can yield specialty gluten free options like bakeries that my partner will be excited to explore–Bunners Bakeshop is one that we’ve been to on a multiple Toronto trips, which I found this way. The disadvantage of this search method is that you can’t really tell why certain restaurants rise to the top–sometimes there will be seemingly nothing gluten free about a restaurant that comes up in the results. And sometimes a restaurant will have gluten free options, but not good food. The google maps search approach also tends to surface a lot of health food spots (not our reason for eating gf), in addition to the western food bias noted above.

Food-first research approaches:

1. This method begins with identifying credible sources–just as I teach my students to do. And because credibility happens in context, I’m not talking about scholarly sources, or anything that’s undergone peer review. I simply want the kind of sources that I trust to prioritize good food, and have been updated recently. I usually use:

- City-specific lists of restaurants. Eater maintains uptodate restaurant lists for most major cities (e.g. Eater Toronto), and for some cities they even keep a gf-specific list (e.g. Eater Portland GF). Some cities also have good local food publications, or local culture magazines that will do a regular feature on restaurants.

- National and international lists. I check the usual suspects like James Beard, Michelin Guide, NYT, and Food & Wine, keeping an eye out for more affordable options (as I teach my students, you need to consider the intended audience of the sources you’re reading, and the intended audience of these lists is often an income bracket or two above an English professor). On this year’s Toronto trip, I sorted the Michelin list for Toronto by price, which brought up PAI, our favorite Thai in the city, as well as some new places I added to my Toronto list.

- People! Family members, friends, foodies, whether in person or online. Here, what’s important is not how much I value their friendship, but how much I trust their palate–I want the folks who are discerning, and share our love of food!

Because most of the restaurants I find via these credible sources are ones I’d be thrilled to eat at, I can quickly move on to the next step:

2. Narrowing the list to likely gluten free. This involves a number of strategies, which I use in different combinations depending on where my research leads.

- Looking for certain cuisines. There are many food traditions that are natively gluten-free, or at least less gluten-centered. We look for Thai, Vietnamese, Mexican, Venezuelan, Japanese, Indian and Ethiopian restaurants frequently, because we know that, regardless of whether they have menu markings for gluten free, they often have gluten free menu items, and less sources of cross-contamination in the kitchen. This strategy led us to try CÀ PHÊ RANG from the Michelin list this year, which was excellent! There are also cuisines we avoid, because they’re much less likely to offer gluten free options, or if they do, they’re less likely to taste good. The avoid list includes French, Italian, and Chinese restaurants (there are always exceptions, but when I’m researching, I usually won’t spend time getting excited about these).

- Looking for certain restaurant styles. High-end restaurants, or restaurants with very ingredient-focused cooking, tend to be more able to accommodate celiac, because there are both fewer things prepped ahead, and a higher level of training for kitchen and front of house staff. For example, a friend in Toronto recommended Myth, which I knew would have a high chance of accommodating celiac. At the other end of the price scale, food halls or collections of food trucks tend to work well because of the wide variety they offer–my partner can almost always find something safe and delicious, and I can choose something different if I want a gluten-filled treat. On our latest Toronto trip, we loved Waterworks Food Hall.

3. Checking for celiac safety. This is the step that I might describe to my students as lateral reading, which is one way to check a source’s credibility. Instead of looking only at the source itself, lateral reading involves checking a number of sources to see if the original source feels trustworthy–in this case, gluten free enough for a sensitive celiac.

- Google Maps–instead of searching “gluten free” in google maps like I used to, I search “gluten” in the reviews of a particular restaurant to see if other diners mention good or bad experiences navigating gluten restrictions there. PAI, our favorite Toronto Thai, has lots of mentions of gluten free, and even celiac.

- Find me GF-while not all restaurants are on this platform, when they are, the reviews are focused specifically on how good the restaurant is at accommodating gf diners, and there is a high level of literacy around celiac specific needs.

- Menu Reading–this is a real exercise in information literacy. A menu can have gluten free options but no gf menu markings (e.g. many thai and indian restaurants), and can also have gf menu markings but not be celiac safe (e.g. a cross-contaminated fryer). I look for menu markings as an indication of some gluten-free literacy, but also look for what types of dishes are cooked in the kitchen to get a sense of cooking methods, ingredients, and cross-contamination risks. Because menus change over time and are represented differently on different platforms, I usually check both google maps photos of the menu, as well as any digital versions of the menu that are listed on the restaurant’s website or online ordering platform. More often than not, there will be dietary menu markings on some, but not all versions of the menu. At PAI, their website menu marks dishes that contain gluten, while a 2019 photo of their printed menu marks dishes that can be made gluten free.

- Contacting the Restaurant–this is a last step that I take only if the above processes leave us feeling uncertain, and I really really want to eat there. If I’m calling, I try to do it at non-peak hours so that whoever answers the phone will have time to check a menu, or ask a chef.

Recording the Research

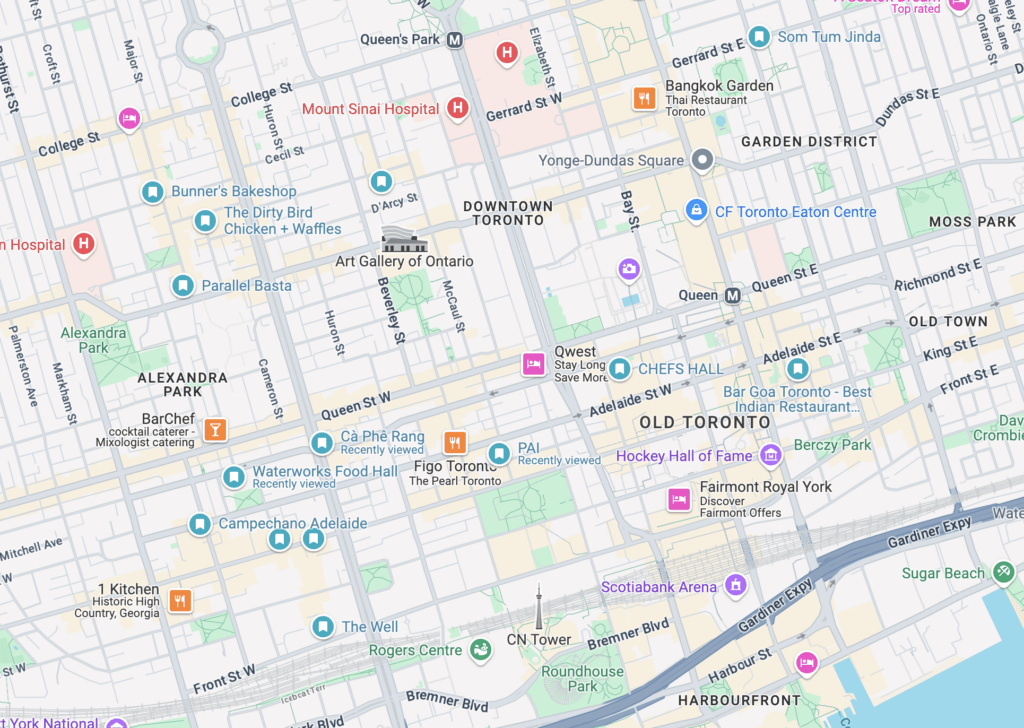

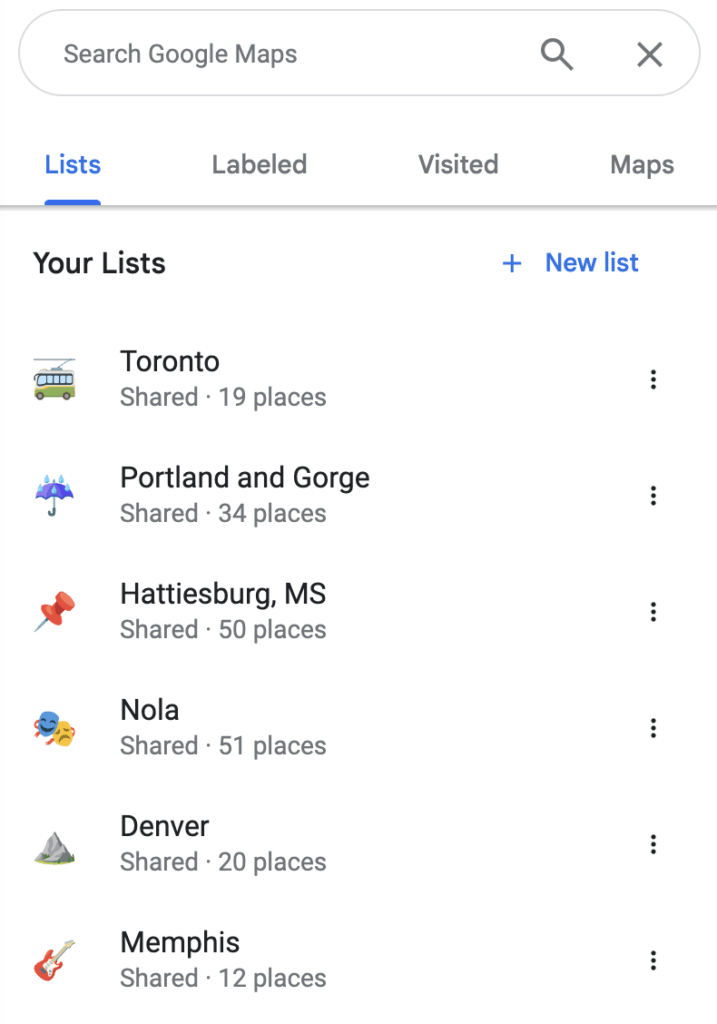

Admittedly, this research process takes a fair bit of time and effort, so I’ve learned the same lesson that I teach my students: it’s important to document your research process and what you learn. I keep a google map of each city we visit, with all of the restaurants I research saved. I also try to add a note (think an annotated bibliography) to remind myself why I chose the restaurant, and what signals suggested to me that it would be a celiac-safe place to eat. This means that when we’re out and about, I can quickly see what options are nearby. And the next time we return to the same city, the research is already begun!

Comments

One response to “Restaurant Research Methods for Traveling Gluten Free”

Wow, glad you enjoy that thorough approach!